Adrian Hemming British, b. 1945

-

Overview

Conscious remembering is historically less significant than the visceral memories registered sensuously by the human body when we seek to explain landscape and its capacity to move us individually.

Simon Sharma

ADRIAN IS AN MA GRADUATE FROM GOLDSMITHS COLLEGE, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON'Painting and printmaking, like poetry and music, still provide the onlooker with direct communication. My work as an artist is profoundly influenced by travel. Travelling is different from going on holiday. I don't travel to find the perfect landscape. Notions of the sublime are no longer the holy grail of the artist. However, the restless nature of travelling and the constant expectation of the next perception informs my work.’Hemming is a landscape artist, not a painter or printmaker of scenic beauty or topographical views, but of nature. He initially pursued studies in engineering before turning his focus to painting. His discovery of plate tectonics and the Nazca Lines and Hieroglyphs in the Peruvian coastal plain kickstarted his deep love for the landscape, which is so evident in his works.

His paintings are characterised by a vivid use of colour and a strong sense of composition. He hovers between abstraction and realism to convey the beauty of natural scenes. His landscapes are not mere representations of specific locations but are imbued with a sense of atmosphere and emotion, inviting viewers to experience the serenity and majesty of the outdoors.As well as painting, Hemming works in other media, particularly printmaking in black and white.Hemming has exhibited widely in the UK and internationally. His work can be found in private collections and public institutions, including:

Ashmolean Museum, OxfordLeicester University, Charles Wilson BuildingUniversity of California, Los AngelesBUPA LondonHeathrow Airport Holding (British Airports Authority)Arts Council, BelfastLincoln CathedralNational Westminster Bank PLCLeicestershire Education CollectionSouth East Arts Collection, Towner Art GalleryKent Education Committee

Paintings £1,000-£10,000

Prints £750 - £1,500 -

Paintings

-

Adrian Hemming, A Sudden Snow Storm Dancing Down the Valley, 2016

Adrian Hemming, A Sudden Snow Storm Dancing Down the Valley, 2016 -

Adrian Hemming, Steel Rigg West, 2015

Adrian Hemming, Steel Rigg West, 2015 -

Adrian Hemming, I stood on a High Place and Looked Over an Endless Plain to a Glowering Sky, 2004

Adrian Hemming, I stood on a High Place and Looked Over an Endless Plain to a Glowering Sky, 2004

-

-

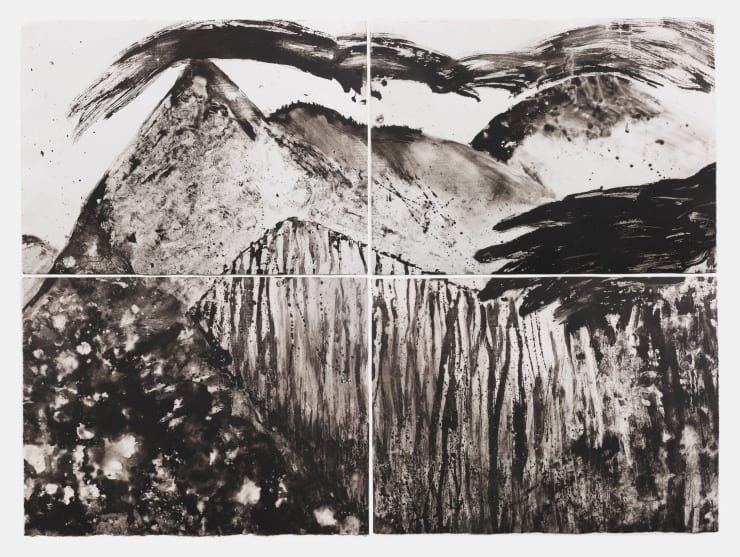

Gran Sasso

-

Border Lands

-

Northumberland Series

-

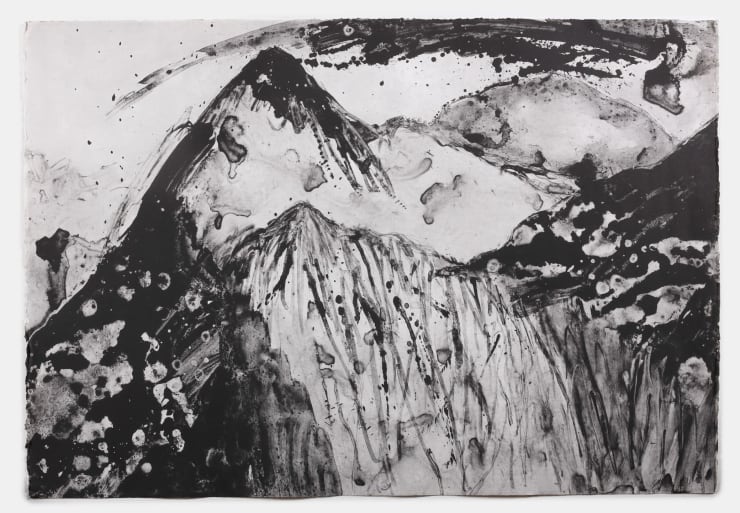

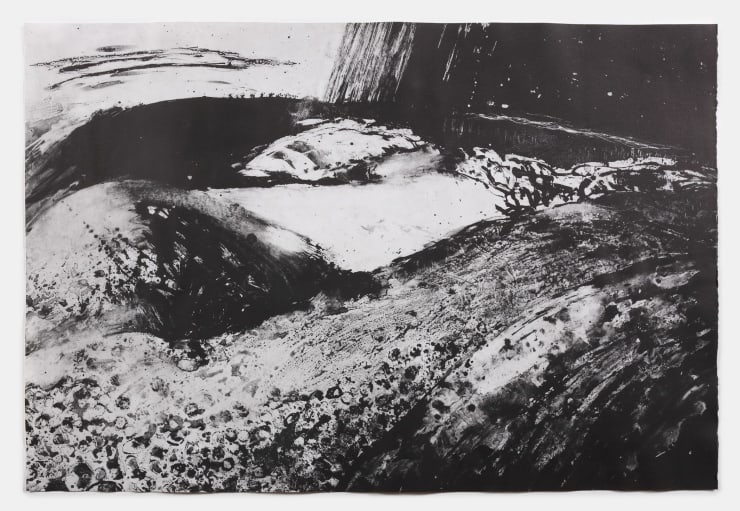

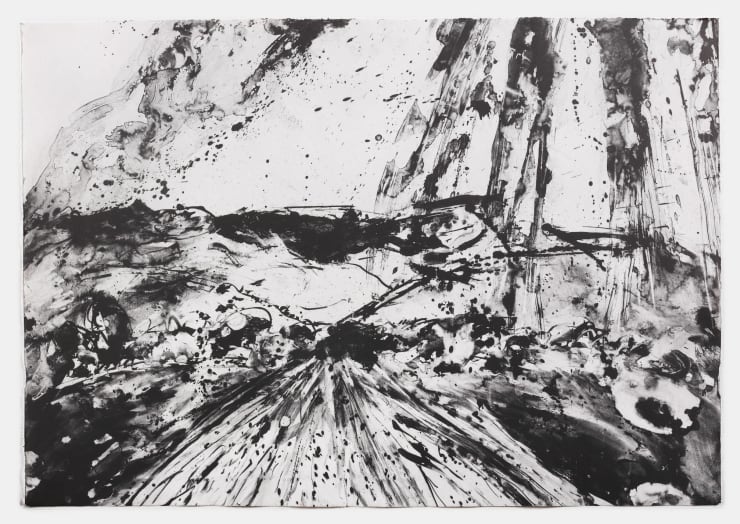

The Order of Time

-

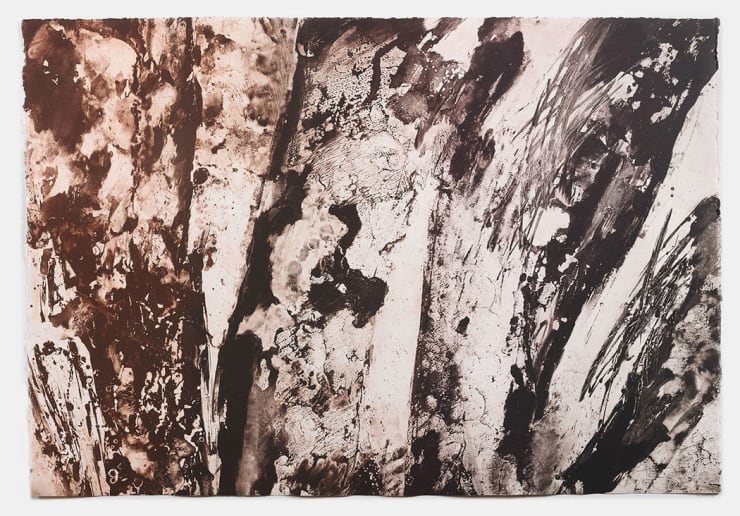

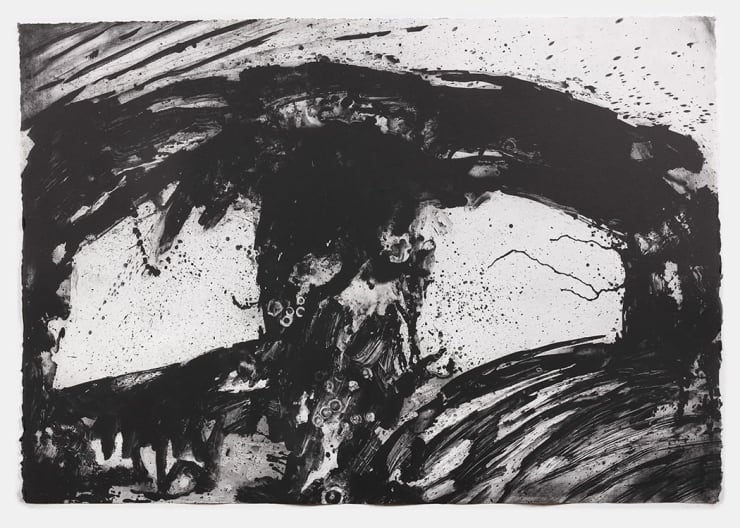

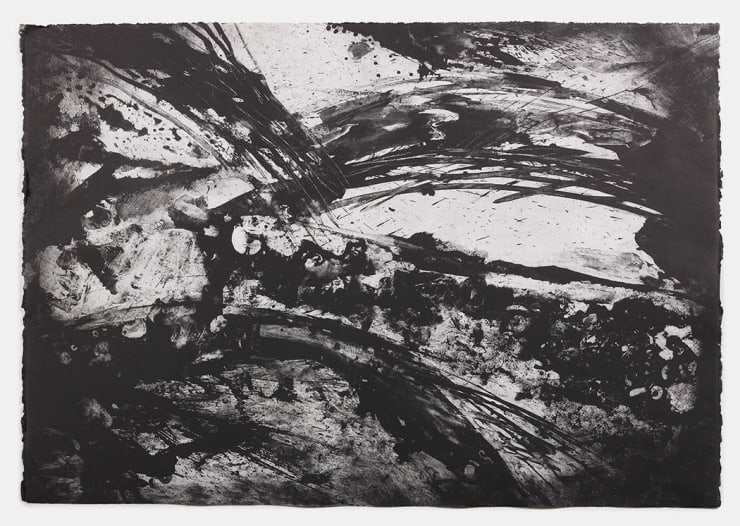

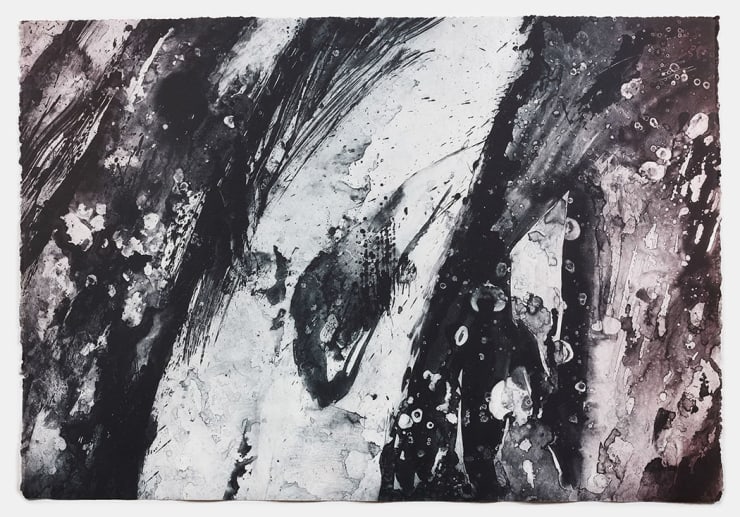

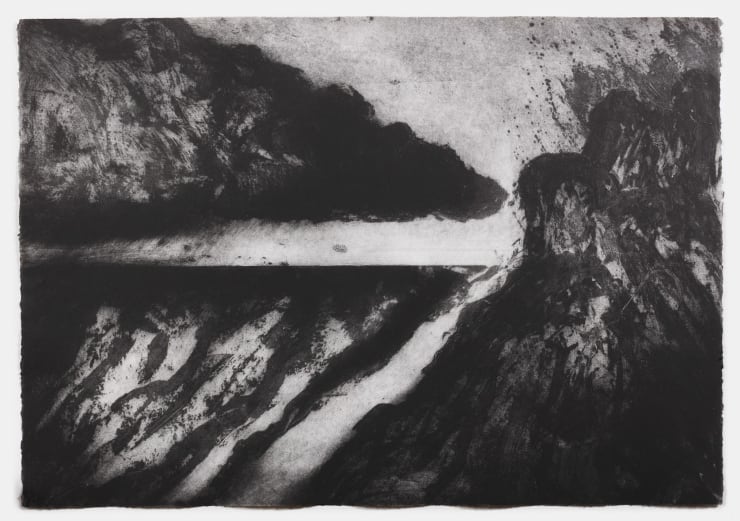

The Order of Time (Text)

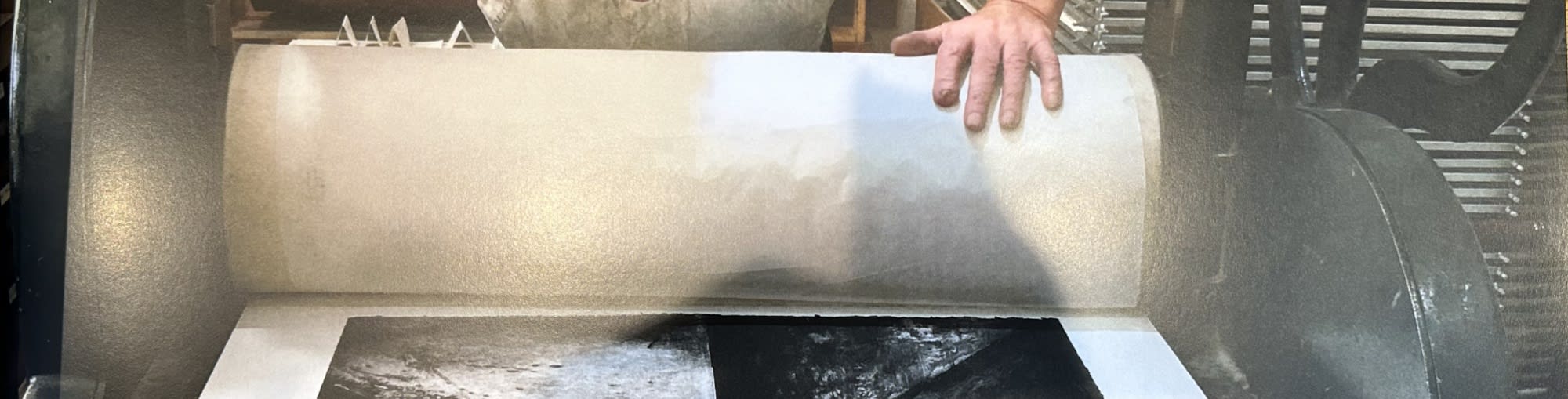

In our latest venture, The Order of Time, a suite of 6 prints, we have exploited the values inherent in photopolymer etching. This unique process can deploy the richest and most subtle range of tones. Combine this with the scale of Adrian's prints, and you have a feast on your hands. For this body of work, Adrian painted on a plastic support film similar to true grain, with Indian Inks, both water-based and non-water-based, to create heavily worked images with an astonishing variety of tonal and surface qualities.

What you don't expect as you process these gigantic plates is the transformation embodied in this particular technique. His original work always looked good, but the print becomes a super-enhanced version. Just as William Eggleston's use of the dye transfer process tips the mundane subject matter over the edge into a semi-hallucinatory experience, Adrian's photopolymer etchings are another kind of transmutation. As my eye glides over the landscape of these massive prints, I am reminded of those silent and surreal sequences of film beamed across space from the Apollo spacecraft as it orbited and recorded the first images of the moon's surface. In Adrian's work, we enter the architecture of the inner world. In a culture dominated by imagery blunted by the binary mathematics of the pixel, Adrian offers an entry into the lost kingdoms of the imagination.

Ian Brown, Volcanic Editions , Brighton , June 2019The Order of Time Series (2019) is a set of 6 large format solar etchings with an edition of 10 for each image. Printed in collaboration with Volcanic Editions. -

The Shipping Forecast

-

Adrian Hemming, Cromarty, Approaching Storm, 2018

Adrian Hemming, Cromarty, Approaching Storm, 2018 -

Adrian Hemming, Forth, Wind Variable, 2018

Adrian Hemming, Forth, Wind Variable, 2018 -

Adrian Hemming, Humber, Good, Occasionally Poor, 2018

Adrian Hemming, Humber, Good, Occasionally Poor, 2018

-

-

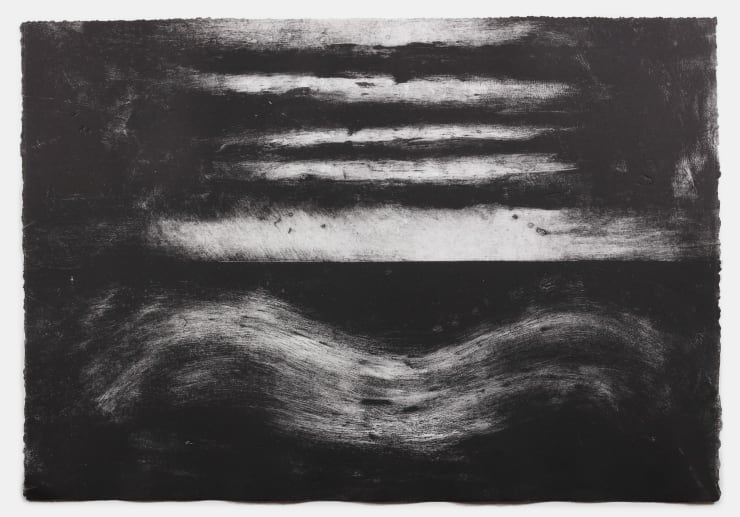

The Shipping Forecast (Text)

Adrian came to my workshop as a painter. His language was that of strong gesture, vivid colour and an accomplished understanding of surface. To make the step from paint into print, we chose carborundum etching. This process enables the brush mark, when delivering resin with controlled viscosity, to offer a range of autographic marks from liquid to stiff whilst loaded with carborundum. Carborundum granules trap pigment allowing the artist to print pure and rich colour, unaffected by the chemistry of the metal plate. I can't say Adrian fell in love with this process (as his friend Hughie O'Donoghue remarked, this is a young man's game) inking and wiping large plates is long and physically arduous. But it made some interesting prints.Next, we dropped the resin and carborundum in favour of large shellacked boards and, working again with a range of products, PVA, heavy structure gel, and heavy carvable modelling paste; we created the plates for The Shipping Forecast. These were made on substantial plates bigger than the largest paper I can get through my press (93 x 62 cms). Printing these ten editions was a steep learning curve. Adrian swiftly understood that making the matrix was just the beginning. His inking up, and more significantly his wiping technique, allowed him to explore the possibilities offered by these plates but also to create another layer of thought on the surface of each print.

Ian Brown, Volcanic Editions , Brighton , June 2019The Shipping Forecast is a series of 10 large format intaglio prints, each 63 x 91 cm, printed on Arches paper using Lawrence's Ultra Black ink. There is an edition of 10 per image. Due to edge-to-edge printing, all are signed, dated, and numbered on the reverse. Although struck from the same plate, each print differs slightly due to the processes involved.The Shipping Forecast is also a BBC Radio broadcast of weather reports and forecasts for the seas around the coasts of the British Isles. It is produced by the Met Office and transmitted by BBC Radio Four on behalf of the Maritime and Coastguard Agency. The forecasts sent over the Navtex system use a similar format and the same sea areas. The waters around the British Isles are divided into 31 sea areas, also known as weather areas. There are four broadcasts per day at the UK local times.

Broadcasting Bands:

Longwave (LW)

Frequency Modulation (FM)

00:48 - transmitted on FM and LW, it includes weather reports from an extended list of coastal stations at 00:52 and an inshore waters forecast at 00:55. It concludes with a brief UK weather outlook for the coming day. The broadcast finishes at approximately 00:58.

05:20 - transmitted on FM and LW, it includes weather reports from coastal stations at 05:25 and an inshore waters forecast at 05:27.12:01 - normally transmitted on LW only.

17:54 - transmitted only on LW on weekdays as an opt-out from the PM programme, but at weekends, transmitted on both FM and LW.

The unique and distinctive presentation style of these broadcasts has led to their attracting an audience much wider than that directly interested in maritime weather conditions.

Origin of names:

Viking, Forties, Dogger, Fisher, Sole and Bailey are named after sandbanks.Cromarty, Forth, Tyne, Humber, Thames and Shannon are named after estuaries.

Wight, Lundy, Fair Isle, Faeroes, Portland, Hebrides, South-East Iceland and Utsire are named after islands. (Utsire is an archaic spelling; in modern Norwegian, it is spelt Utsira)

The German Bight is an indentation on the Northern European shoreline.

Dover and Plymouth are named after towns.

Rockall and Fastnet are both named after islets.

Malin is named after Malin Head, the northernmost point of Ireland.

Irish Sea is named after the Irish Sea.Biscay is named after the Bay of Biscay and Trafalgar after Cape Trafalgar.

Fitzroy is named after Robert FitzRoy, the first professional weather forecaster, captain of HMS Beagle and founder of the Met Office.

-

-

ADRIAN IN CONVERSATION

PATRICK DAVIES TALKS WITH THE ARTISTWHEN DID YOU REALISE YOU WANTED TO BECOME AN ARTIST, AND WHY DID YOU CHOOSE PAINTING? DO YOU COME FROM A CREATIVE BACKGROUND?Always, right from when I can first remember. I don't come from an artistic background, but my younger brother and I were always designing cars, boats and planes. I left school at fifteen and could have gone to a form of art college, but Mum wanted me to have a proper job. So I became an Apprentice engineer.WHERE AND WHEN DID YOU STUDY AT ART SCHOOL? WHAT WAS THE EXPERIENCE LIKE AND WHAT DID YOU LEARN?I first went to Lincoln Art School to do a Foundation course. However, I hadn't passed any exams, so I couldn't get a grant if I applied for a BA. I studied O and A levels at night school and my Foundation during the day. I just scraped through. That year changed me profoundly and super-charged my desire to be an Artist. I learnt to grow up. After Lincoln, I studied for a BA at Brighton, then a decade later, an MA at Goldsmiths, London University.YOUR SUBJECT IS EXCLUSIVELY LANDSCAPE. WHY IS THIS, AND WHAT INFLUENCES FEED INTO THIS NARRATIVE?It is now, but I started as a sculptor using contemporary forms and materials. Then, figurative painting took centre stage. During the 1970s, I discovered plate tectonics and the Lines and Hieroglyphs at Nazca. Simon Schama said, 'Conscious remembering is historically less significant than the visceral memories registered sensuously by the human body when we seek to explain the landscape and its capacity to move us individually'. This is my Landscape.IT IS ONLY RECENTLY THAT YOU HAVE STARTED TO MAKE PRINTS. WHAT PUSHED YOU IN THIS DIRECTION?At art school, I hated printmaking. I found it so frustrating. The time, the processes, The attention to detail. I just wanted to get on with it and slap some paint about. I've been making prints as a serious consideration for about five years now. Finding Solar printing was a revelation right up my street.SOLAR ETCHING IS A VERY INTERESTING PROCESS. HOW DOES IT WORK?Instead of using acid to etch a line into a steel plate, you use sunshine or powerful UV light. You buy a steel plate from the manufacturers with a layer of chemicals on the surface. You then create an Aquatint print by laying a special film over the plate and subjecting it to UV light. This creates millions of irregular invisible pits in the steel plate capable of holding ink. In the meantime, on a sheet of mark resist film, you make your drawing, placing it over the aquatint again subject to UV light. This will harden some areas; wash the plate off with warm water and leave it in sunlight to solidify. The plate is then ready for inking up and printing. It's a very direct process between the drawing and the Print.YOUR PAINTING IS KNOWN FOR ITS VIVID HUES, BUT YOUR PRINTS ARE MONOCHROMATIC. IS THERE A REASON FOR THE ABSENCE OF COLOUR?Yes, when I draw plein air, I emulate Van Gogh. That is, I cut sticks or reeds into pens and use Indian ink to make the drawings. I like the rigour of black and white and all the shades in between. So, when making the print, I'm very conscious of history and the aesthetic considerations that work with these processes.WHICH OTHER ARTISTS DO YOU ADMIRE AND WHY? DO ANY DIRECTLY INFLUENCE YOUR WORK?Ivon Hitchens was a very early influence. I still admire his work. Titian is God. Goya is brilliant, and so is the great Turner. I see things in all artists to a greater or lesser degree. Something, like reading a book, will always affect you. Some artists, even when incredibly popular, you won't like, and you have to ask yourself why. Just to be dismissive is not good enough. Anselm Kiefer is fabulous.DO YOU WORK ON MULTIPLE IMAGES AT THE SAME TIME?Yes, mainly when I paint. I usually work on several images simultaneously, jumping from one picture to another. I typically have a pair, three, or four works dealing with the same subject matter on the go.IS IT IMPORTANT HOW THE VIEWER REACTS TO YOUR WORK?Not really. I've been at the coal face for so long. Of course, it's lovely to get the slap on the back, particularly from someone you admire. I can only pour my heart and soul into the work and hope the viewer sees something in it.WHAT OTHER INTERESTS DO YOU HAVE?I love to cook, I love the pub and of course travelling. I still read avidly. However, music, which I adore, for some reason, doesn't play a big part in my life. -

Andrew Marr, Broadcaster and Author writes about the artist

Andrew Marr and Adrian Hemming are long-standing friends. In 2017, they exhibited together under the title 'The Hemming & Marr Show'.

Painting is necessarily a solitary occupation. Everything that matters most about it takes place silently in the painter's brain. In the studio, when the hard work is being done, the silence is absolute.And yet every painter needs to talk - needs help, needs criticism, needs a frank and knowing friendship. So, when I began to try to paint seriously after I had suffered a stroke, Adrian Hemming's friendship was both wonderful luck and a lifeline. He comes into the studio, raises a quizzical eyebrow, perhaps shakes his head about something that had pleased me, and quietly, gently suggests other directions I might follow. And he's always right.Adrian and I started talking because we live close to one another, have numerous mutual friends, and do not fanatically abjure Pale Ale. But the basis of our friendship and relationship is painting, painting, and painting.I always call Adrian, with a slight note of jealousy in my voice, "a proper painter". Unlike me, he has gone through a full and rigorous training. He has devoted his entire life to mastering pigment and surface, design and meaning since his teenage years. And, by God, it shows. Working in his Islington studio, he is meticulously picky about the colours he uses and mostly grinds for himself. (The Unison Company of Northumberland's A19 Ultramarine is a particular favourite.) The walls around him are hung with the latest work, which is always and forever a work in progress: Adrian is a great believer in the virtues of pitiless obliteration. Anything that may seem easy about his painting has been very hard won. In fact, one of the first lessons he taught me was that even what one might consider to be a fine passage of painting - square inches one is quietly delighted with - must often be overpainted or rubbed out in the higher interests of a completed work.This way of painting produces a surface that must be looked at near at hand. What I particularly value in Adrian's art is the rich, rucked textures and the densely worked, scored, and often extremely complex surface areas he achieves. Let me explain why I think this matters so much. We live in a world dominated by flat, glossy, glassy screens. Today's digital manipulation is boundless and endless. And, just as with the original invention of chemical photography in the 19th century, this technical revolution throws problems to today's painters.How does handmade, traditional art respond? Should we become video artists? Should we give up pencils for apps on the iPad? Both of us believe that the flatness of the digital world must send painting in the opposite direction, back to the claggy materiality, the "thisness" of oil and pigment. To be radical today is to insist on the organic essence and origins of the tradition, and I would argue that you can read this very clearly in the texture of a Hemming. This means that you need to look at these pictures in this show: reproductions, however good, are not nearly enough. But - and this is not a skill I have yet achieved - Adrian's densely worked passages occur only in harmony with larger areas of calm. The frenzy is more frenzied when surrounded by lapping, quiet blues or greens.Although we mainly discuss the craft and physicality of painting - about pigments, bristles, different oils, and glazes - Adrian Hemming is a philosophical painter, much concerned with myth, the environment, and the nature of perception. Above all, he is trying to answer the most challenging and vital question a painter faces, which is simply: "What should fresh painting look like?"All of us who paint, paint with the huge weight of the Western tradition sitting on our shoulders. At times it can seem as if every idea has been had before. Perhaps every design, motif, and colour combination has been done better already; perhaps all that is left, even for a serious and honest painter, is a quotation. Adrian, like me, is a fascinated and obsessive looker, a haunter of exhibitions by greats. When we flop down in our nearest pub - the Lansdowne in Gloucester Avenue - we are often talking about the latest Rauschenberg show, or Howard Hodgkin or Peter Lanyon or Patrick Heron. Adrian was taught by, among others, the painter I would regard as the most successful non-representational living British artist, Gillian Ayres. Yet he has managed that great feat: a Hemming, whatever its size, shape and colour range, looks like a Hemming and nothing else. He has absorbed, ingested and then quietly gone his own way.I admire him so much for that. Since my stroke, I have had a much more intense sense of the importance of going your own way. Not a day passes when I don't think about how little time is left, and for me, this means a redoubled effort to paint better because it is the best way of expressing my personal sense of what it means to be alive. Although this might seem a somewhat solemn undertaking, and it is certainly a strenuous one, it is, in fact, full of joyousness. When I am painting badly, I drive myself into a rage. But when I am painting well, I feel full of delight. A big part of that delight has come about thanks to the calm, wise friendship and peaceable advice given to me by Adrian Hemming. A lesser man would have tried to encourage me to paint just like him: Adrian has helped me to paint like me, only better - a much harder task. As you observe these pictures, I hope you see the story of an artistic friendship, too.

Andrew Marr, London 2017