Jack Dunnett Scottish, b. 1995

-

Overview

The way events, stories, myths, and memories evolve through oral tradition, documentary and artistic depictions is always interesting to scrutinise. It's like a perpetual wheel that turns not metaphorically - untouched by intervention - but like a physical rolling stone in travel.

JACK IS A 2017 GRADUATE OF GRAY'S SCHOOL OF ART, ABERDEENDunnett creates enigmatic stories using placed figures that awkwardly meld and jar, framed inside scenes that appear to be staged. He merges traditional oil painting techniques with random reactions between household chemicals, building materials and found pigments. Working with processes that build up and strip away layers, Jack examines relationships between prescriptive mark-making and chance elements, combining structure and chaos to create imagery that holds itself in balanced tension.

The culmination is work produced on small, intimate boards that present as informative and questioning, demanding that the viewer decode each picture for a unique and personal interpretation.

An exhibition of new work will open in April 2025, which includes a critical text by Julian Spalding, the former Director of Glasgow Museums and founder of the Glasgow Gallery of Modern Art. Now a world cultural historian.

Please email the gallery for information about paintings currently for sale.

An exhibition of new work will open in April 2025, which includes a critical text by Julian Spalding, the former Director of Glasgow Museums and founder of the Glasgow Gallery of Modern Art. Now a world cultural historian.

Prices range for paintings £800 - £1,200 -

Works

-

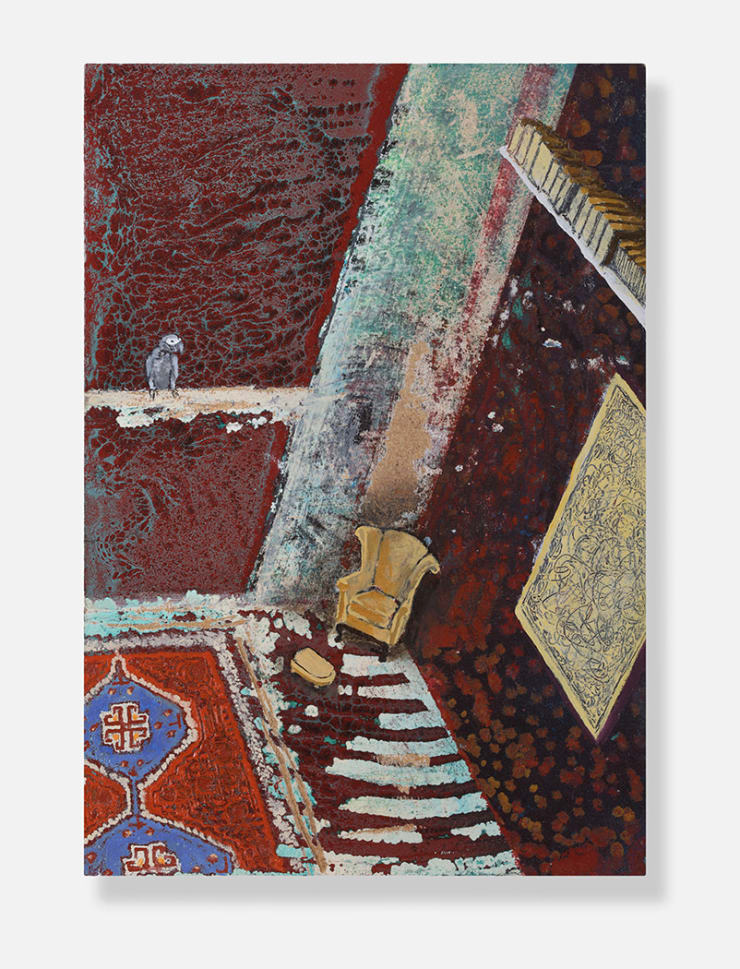

A Big Hole, 2024

A Big Hole, 2024 -

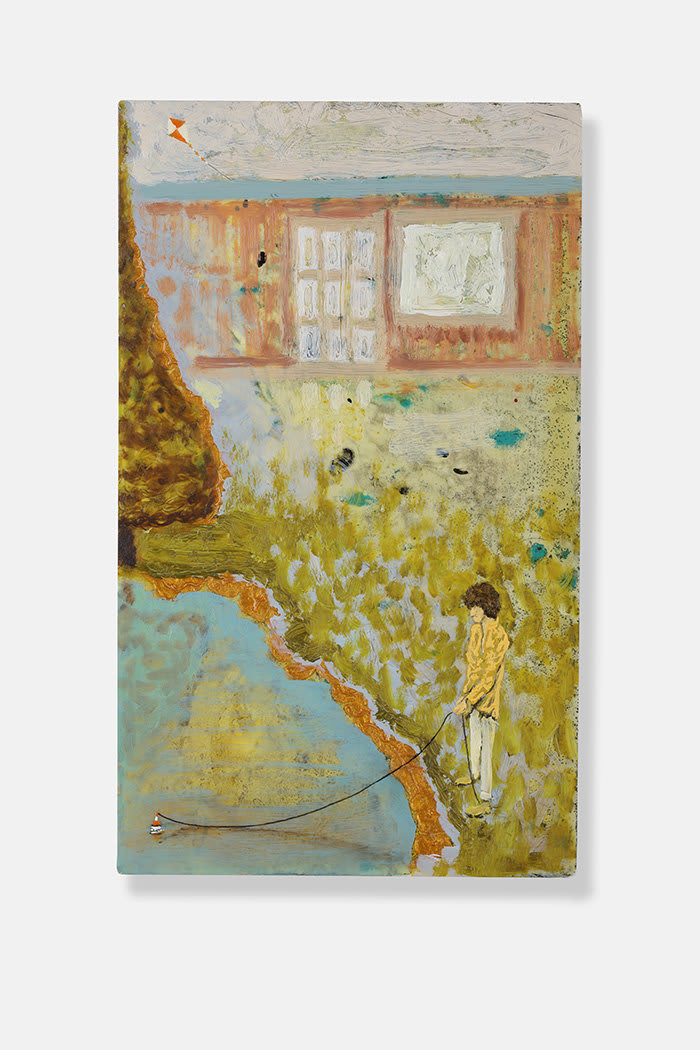

A Windfall So Stratospheric It Heavies the Heart, 2021

A Windfall So Stratospheric It Heavies the Heart, 2021 -

Aspiration and Floundering, 2024

Aspiration and Floundering, 2024 -

Before The Bathwater, 2023

Before The Bathwater, 2023 -

Bouldering, 2024

Bouldering, 2024 -

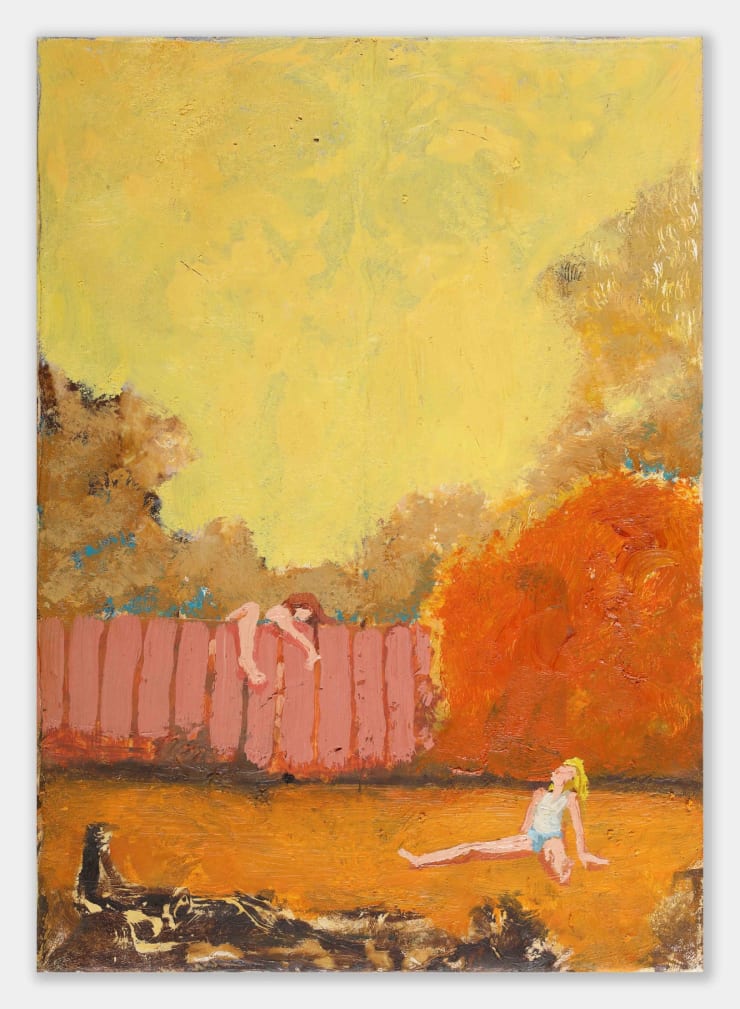

Following the Fun, 2023

Following the Fun, 2023 -

Post Boy, 2024

Post Boy, 2024 -

Quaking Aspen, 2022

Quaking Aspen, 2022 -

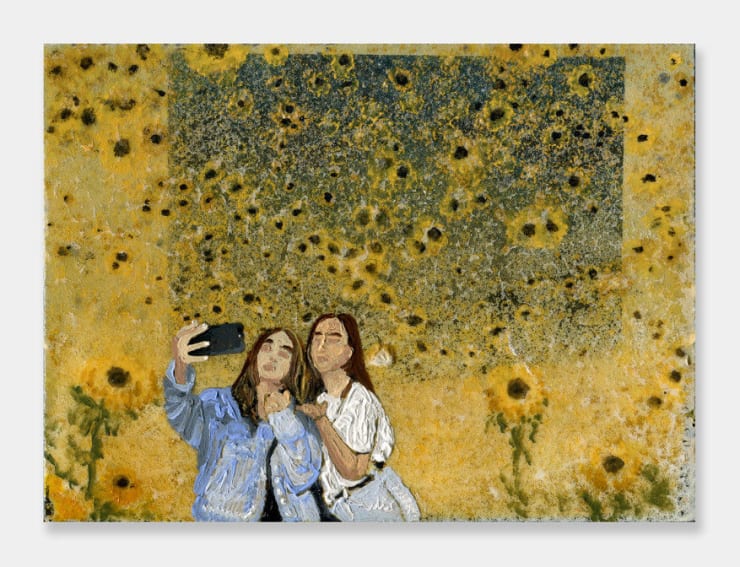

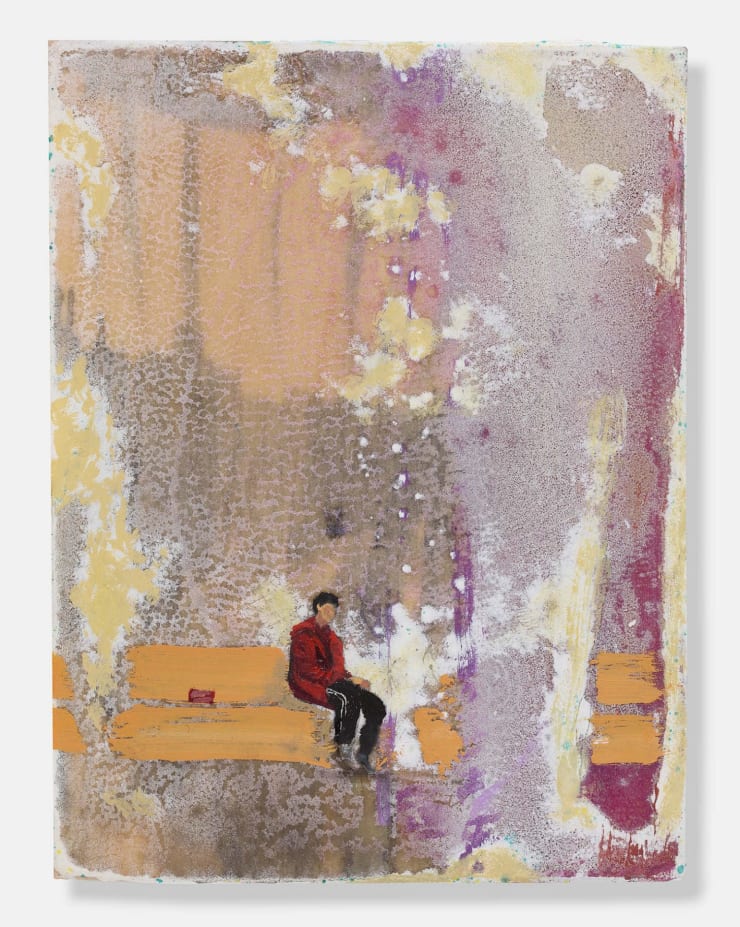

Self-worn Us, 2023

Self-worn Us, 2023 -

Spectacle, 2023

Spectacle, 2023 -

The River was Deep, 2024

The River was Deep, 2024 -

The Crossing, 2023

The Crossing, 2023 -

Salt and Batter, 2023

Salt and Batter, 2023 -

Ratlands, 2023

Ratlands, 2023 -

Born for This, 2023

Born for This, 2023 -

Viñeta 6, 2023

Viñeta 6, 2023 -

Viñeta 8, 2023

Viñeta 8, 2023 -

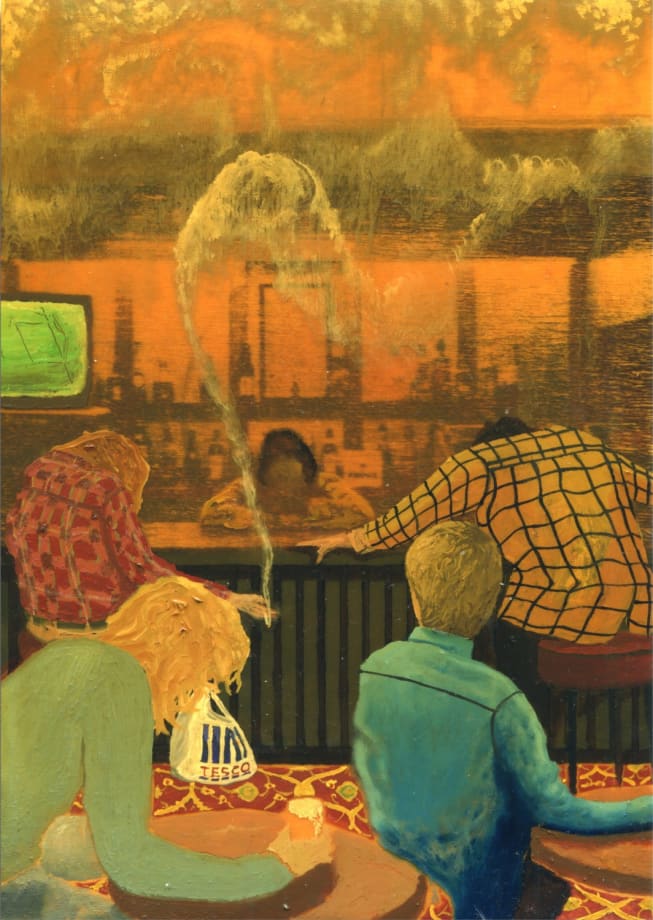

Sharon's Suffering and the Brigadeers, 2020

Sharon's Suffering and the Brigadeers, 2020 -

The Comfort of the Morning - nfomercia, 2020

The Comfort of the Morning - nfomercia, 2020 -

Weeping Song, 2019

Weeping Song, 2019 -

The Performer, 2018

The Performer, 2018 -

Drippings from the Ceiling, 2018

Drippings from the Ceiling, 2018

-

-

-

Jack in conversation

Patrick Davies talks to the artistWHEN DID YOU REALISE THAT YOU WANTED TO BECOME AN ARTIST? DO YOU COME FROM A CREATIVE BACKGROUND?

I've always drawn for as long as I can remember. Getting ideas onto a piece of paper with marks seemed intuitive and a direct way to try and put something tangible to the things going on in my imagination. I'm an only child, and I remember when staying at my grandparents' cottage at weekends, my grandmother let me draw on this Woolworths A4 notepad she used for shopping lists. I saw where she returned it to afterwards and would take it out to continue drawing tiny little images smaller than a playing card, and once I lost interest in whatever the idea was, I turned to a crisp new clean sheet. I soon used every page in the book, and she bought me a drawing pad of my own. When I was slightly older, maybe from around five or so, my father would set aside half an hour where we would draw together in the evening, this time sketching actual things from real life or memory. I could easily be kept quiet and entertained by paper and a pencil. I didn't understand the point of colouring books because of their prescriptive nature. Using a set number of colours to fill in someone else's picture was boring and pointless, as it would end up looking the same as before. Art classes at school, where everyone had to make something like a hand-print turkey, were of no interest. Everyone's always looked the same, and it seemed a severe waste of time. I never realised that I wanted to be an artist because, as far as I was informed, it wasn't a job. You couldn't apply to be an artist and get a salary. I was aware that there were people in the past who were artists, but of course, they lived far away and died poor. I knew there were people locally who made art, but apparently, they did it as a hobby and worked a 'real' job to get money. I was told that some artists could make a living from their work, but they were one in a million, and the clear implication was that I was not. I only found out that at fifteen, that art school was a thing that existed. So, I decided to apply.

WHERE AND WHEN DID YOU STUDY AT ART SCHOOL? WHAT WAS THE EXPERIENCE LIKE. WHAT DID YOU LEARN?

I studied Painting at Gray's School of Art in Aberdeen from 2013 to 2017. Being from a small town in the far north of the Highlands, Aberdeen was the big city for me and an exciting prospect. The buildings had more than two storeys, and shops were open on Sundays. There were even two Wetherspoons', and multiples of every different kind of supermarket, some even open 24/7. I had moved to a bright orange breezeblock prison cell with seven strangers and one fridge in a compound of hundreds of other students raring to make their own mistakes. It was brilliant. It was such an odd, choppy experience, though, attending art school at eighteen. I vowed to be open-minded and try to dip my toes in every area of study. In the first year, we all had to do a generalist course which involved studying things like fashion, architecture and communication design, which I already knew I had little interest in. Even the one day a week of life drawing just involved sketching a pile of chairs and easels in the middle of a hall. At the same time, tutors from all different departments would walk around and whisper contradictory information in your ear. I decided my time would be better spent doing independent study for most of the week. I spent my days going around Aberdeen’s old pubs and dive bars with my sketchbook, a book to read and my music player. I'd spend my student loan on pints of heavy and sit in a corner drawing and writing, listening to music and people. There was a certain honesty and lack of pretence to those I'd meet, and that was such a contrast to art school with the students pretending to be adults and the tutors who had the gall to claim that making a giant model of a clothes peg out of cardboard boxes would 'feed into our creative practice'. Before attending art school, I naively imagined it would be a caricature of a place, a sort of free-for-all of encouragement and creative expression. It turned out to be a far more structured affair, for the first two years at least. After that first year, I began to concentrate properly on my studies and show up to the studio as I now had a space of my own. Having the time and the space to work and having artists as tutors imparting their knowledge was invaluable, and I knew it wasn't to be taken for granted. Whether it was advice that deeply resonated with what I was searching for or disagreements about specific approaches, it allowed the possibility for growth if taken in the right way.

WHAT ARE THE MAIN INSPIRATIONS FOR YOUR WORK?

I draw a lot from stories and the paint's physical properties. When it comes to subjects for paintings, they're informed by a steady stream of influences that come from many sources. The films I watch, books I read and music I listen to all feed in alongside memories, musings and day-to-day experiences. I see as much art as I can and am drawn to small details of texture and colour. Marks that convey the hand of the artist often grab my attention and make me think about the degree of control the artist can have over the materials and what level or expression is most appropriate to convey the subject.

I have countless areas of inspiration. I dart between them so frantically that I'm often not immersed deeply in one particular subject but find myself skimming between something that links multiple interests. Stories and how we interact with them; the mundane and the transcendent; signs and symbols; honesty and allegory. The only constant is that feeling that doesn't go away, that says, 'This painting needs to be painted'.

I'm interested in the documentary, the human element of how events or stories are told by the person capturing them. Filmmaking, for example, varies drastically and has noticeably changed over time due to different sensibilities and motives. A documentarian has the choice of delivery of their subject, from a cold, matter-of-fact articulation which values subjectivity to using musical and narrative interjections to affect a specific area of emotional response from a viewer, aligning them with the artist's viewpoint.

Looking at a painting as a staging that can only ever imitate life, I try to touch on the absurdity of that notion when drawing together different areas of inspiration. Sending figures taken from different films or photographs into a setting taken from my memory and having them interact with ideas from a short story will immediately lay out a starting point for something new to happen. From this, I can let the piece take me through multiple variations of the elements within. I can work with them to form a resolution through layers of addition and redaction while allowing the materials to intervene with chance.

Because of the physical limitation of edge on a painting, I've been drawn to looking at how actors are moved in space on stage and screen. Both mediums have similar limitations of edge that are solved in different ways. Where the stage director moves their players and lighting to achieve a particular atmosphere, the film director can also move the viewer. In painting, I often aim to combine a film director's dynamic range of movement with theatrical use of lighting. Merging these with the painter's license to skew perspective and manipulate colour can work to create an atmosphere within a work that can appear both familiar and uneasy.

HAVE YOU ALWAYS WORKED ON A SMALL SCALE? HOW IMPORTANT IS THIS TO YOUR CREATIVE PROCESS? DO YOU WORK ON PAINTINGS ONE AT A TIME OR IN SERIES?

Working on a small scale has gifted me a lot of discoveries, none of which I anticipated or sought out. I first began making small paintings in my final year at art school. I had an overarching outcome in the back of my mind for what I wanted my degree show to be in the years before I even began thinking about the practicalities of it. It needed to be on a large scale involving a scene on a 2x4 meter canvas, encompassing many figures which showed a modern narrative in a grandiose Romantic setting, reminiscent of a Turner or John Martin painting. Over time, however, while making individual character studies for these large works, I wanted to explore these snippets in more depth, keeping them self-contained yet involved in an ongoing narrative. The Romantic paintings I had been studying may have deployed many figures in a large painting, but that tended to emphasise the fundamental proponent ideals of what Romanticism was yearning to achieve in its time, the diminutive form of human within nature, and nature as the signifier of overarching divine superiority. The characters I had been delving into needed their own platforms, which were more conducive to our contemporary situation. Isolated characters were explored in depth as part of a larger whole, yet eternally separated from it. Each piece is set in its own amber, to be looked at alone, defined by its own edges and limitations, yet continues to be part of the larger overarching body of work. Characterised by the grounded limitation of edge, restricted by their four walls, yet linked with a serial bond that they will be forever unaware of.

Working intimately on small boards has led me to a specific way of painting while holding or balancing them on my fingertips. It allows me to quickly change the angle I'm working at without adjusting an easel to move around the studio as I work, seeing the piece in a different light. My palette is on wheels, so I roll it around the room as the light shifts. When I've taken a piece as far as I can go with it intuitively that day, I'll place it down and start working on another picture. I've found this the best way to avoid creative blocks or dead ends. I work on up to fifty paintings at once. All take a long time to complete, but this rotational work stops anything from feeling monotonous or laborious.

THE TECHNICAL SIDE OF YOUR PRACTICE IS IMPORTANT, OFTEN COMBINING TRADITIONAL MATERIALS WITH OTHERS NOT NECESSARILY ASSOCIATED WITH PAINTING. WHAT ARE THESE, AND HOW ESSENTIAL ARE THEY TO THE FINISHED WORK?

I've come to utilise a short list of household chemicals in my work just as much as any particular oil colour. They all stemmed from heavy-handed experimentation with materials when I was at art school and worked part-time in a hardware shop. Behind the counter was this laminated sheet of pictures of different problems people would encounter with paint if misused. Things like 'surfactant leeching', 'rippling', and 'blistering'. It reminded me of the books you'd get in high school that showed photographs of painterly techniques; 'scumbling', 'sgraffito', 'impasto' etc. I brought this knowledge to the studio, along with discounted burst bags of building materials, defective tins of paint and various volatile industrial chemicals. I've pared these down over the years, as the first experiments occasionally resulted in inadvertently burning a hole in the studio floor, accidentally synthesising chemical weapons and creating paintings which were 'hot to the touch' and couldn't be exhibited for public liability reasons. All these initial compounds are gone from my work. However, looking up their less powerful chemical counterparts has led me to certain salts and light acids, which significantly affect the patina of my work. I've learnt that the bones of the piece has to be the paint, but there are a lot of domestic paints, which I find a lot more hard-wearing and effective than the most expensive oils. For example, liquid rubber used for roofing makes an excellent deep matte black. I also paint it on my boots to keep them from letting water in the cracks. Some brands of plaster used in the trade are much stronger than artist's plaster and can be used to make fresco-type pieces which can stand the test of time. The best way to get the effect of a cement wall in a painting is to use cement.

WHICH ARTISTS DO YOU ADMIRE AND WHY? DO ANY DIRECTLY INFLUENCE YOUR WORK?

There's a lot. Philip Guston, Rose Wylie and Louise Bourgois for the way they talk about painting. Antoni Tàpies, Anselm Kiefer, Kai Althoff and Merlin James for their use of materials surrounding painting. Hopper, Vuillard and Turner for their use of colour. Walter Sickert, Andrew Cranston, Norbert Schwonkowski and Frank Auerbach for their manipulation of paint. Emin, Munch, Schiele and Bacon for their rawness and honesty. Caspar David Friedrich, Carl Spitzweg and Carl Gustav Carus for their compositions. They've all influenced my work directly to some degree. I like how certain filmmakers talk about creating images and working with narrative. Charlie Kaufman and Tarkovsky write excellently about the process and the thoughts behind them, and they speak in terms which often cross over with painting. Many performers, comedians and musicians also talk so well about the creative process that I take a lot from their words: Patti Smith, Stewart Lee, Nick Cave, and Aidan Moffat. I'm a sponge when listening to folk talk about their work. The feeling of a shared experience in the arts, however much I can relate to it or not, is always cathartic.IS IT IMPORTANT HOW THE VIEWER REACTS TO YOUR WORK?

First and foremost, I need to make the work for myself.

I avoid taking responses to my work too seriously. I do pay attention to comments, compliments and critiques from those I respect, and I appreciate them along with kind words from people who take something from my pictures. I don’t tend to dwell on responses. I don’t take praise very comfortably. I enjoy hearing what people think, particularly when it triggers something in them that resonates with what I had in mind while making the work. My paintings are ambiguous, and anything they reference from my life will inevitably be inaccessible to the viewer. I don’t want people to be locked out but to be able to explore the piece and take from it what they will.

WHAT OTHER INTERESTS DO YOU HAVE?

Painting is most of every day, and thinking about it is the rest. I like walking around somewhere that's green and taking trips when I get the chance. A visit to a city with a good collection of art, a substantial park, and some decent music in the evening will keep me entertained. Good books, films, and friends make up a great day. -

-

-

Film