Jack Dunnett: Edgelands

-

-

Paintings

-

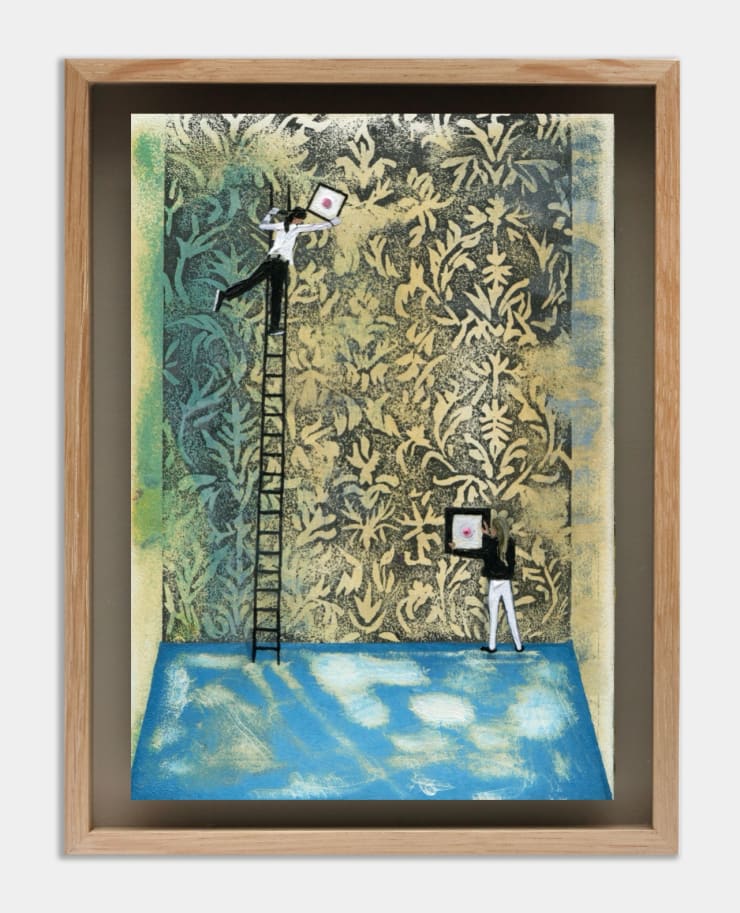

Jack Dunnett, A Little Souvenir, 2025

Jack Dunnett, A Little Souvenir, 2025 -

Jack Dunnett, A Relentless Spirit, 2025

Jack Dunnett, A Relentless Spirit, 2025 -

Jack Dunnett, Anxious Sanctions, 2024

Jack Dunnett, Anxious Sanctions, 2024

-

Jack Dunnett, Beauty for Ransom, 2024

Jack Dunnett, Beauty for Ransom, 2024 -

Jack Dunnett, Benign Consultations, 2024

Jack Dunnett, Benign Consultations, 2024 -

Jack Dunnett, Cool Babies, 2024

Jack Dunnett, Cool Babies, 2024

-

Jack Dunnett, Darts, 2025

Jack Dunnett, Darts, 2025 -

Jack Dunnett, Generations to Come, 2024

Jack Dunnett, Generations to Come, 2024 -

Jack Dunnett, He Thought He Looked Nicer in Foreign Mirrors, 2025

Jack Dunnett, He Thought He Looked Nicer in Foreign Mirrors, 2025

-

Jack Dunnett, Hedgehog Dilemma, 2024

Jack Dunnett, Hedgehog Dilemma, 2024 -

Jack Dunnett, Knew a Dresss, 2024

Jack Dunnett, Knew a Dresss, 2024 -

Jack Dunnett, Millennium, 2024

Jack Dunnett, Millennium, 2024

-

Jack Dunnett, Nothing Ever Happens, 2025

Jack Dunnett, Nothing Ever Happens, 2025 -

Jack Dunnett, Patchwork Belongings, 2024

Jack Dunnett, Patchwork Belongings, 2024 -

Jack Dunnett, Poison as Patience, 2024

Jack Dunnett, Poison as Patience, 2024

-

Jack Dunnett, Public Speaking, 2024

Jack Dunnett, Public Speaking, 2024 -

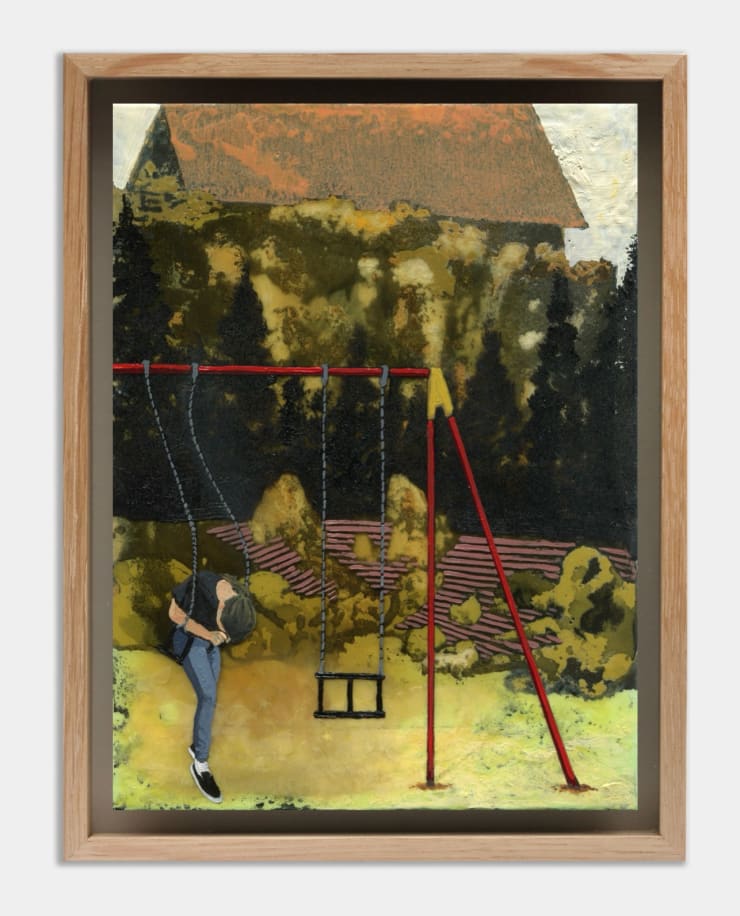

Jack Dunnett, Ride On, 2024

Jack Dunnett, Ride On, 2024 -

Jack Dunnett, Shelved and Portrayed, 2024

Jack Dunnett, Shelved and Portrayed, 2024

-

-

Artist Exhibition Statement

When creating this new body of paintings, I found myself looking into a past that was not fully mine, and not really in the past. As I sat with blank surfaces they seemed as if they were demanding more of me than I had planned to paint about. Scenes and ideas that I had in my mind concerning stories and allegory were slowly realised, but they brought with them remnants of spaces and figures from my memory. Things which I had always planned to paint at some point, but not yet.

Places from my childhood cropped up. Places I remember that felt like they had 'quantum leapt' out of their era and held memories that were too heavy for them. Playground equipment that was decades out of date even when I was young, threatening tetanus and concussions. Rooms of dated wallpaper, re-papered poorly with a new set of dated wallpaper. A sporting ground that never witnessed a net that wasn't within a 24-hour window of combustion. Arenas of defunct design, clearly utilised yet never having the purposeful arrow of regeneration aimed at them.

And then the landscape stands, larger than all of that if only on a different timescale. Uncaring to bashes and purposes. Changing every day in colour and form with the dramatic banality of the movement of the sun. It's blocked off by walls through necessity yet it's influence seeps in through the cracks.

And then the people stand, with the most unfortunate timescale of the bunch, with their stories, plans and feelings that beg and demand an impact far outside their grasp. Flirting knowingly with what their perception could call absurdity if they felt like attaching a word to it.

The paintings I've made are a selection of stories which hold themselves slightly out of time and place in their staging, but I hope speak to timeless human concerns. -

Essay By Julian Spalding

EdgelandsJulian Spalding is a former director of art galleries for Sheffield, Manchester and Glasgow. He established the Ruskin Gallery, the St Mungo Museum of Religious Art and Life, the Gallery of Modern Art Glasgow and the Campaign for Drawing. His many books include The Poetic Museum, The Eclipse of Art, The Art of Wonder (winner of the Sir Banister Fletcher Prize 2006), Con Art, The Best Art You've Never Seen, Realisation and, with Raymond Tallis, Summers of Discontent.

It's a delight to see the art of painting re-emerging. There were times when I thought I'd never live long enough. But now it's happening. Merlin James, Sourav Chatterjee and Jay Rechsteiner are just a few of many names to conjure with in this renaissance. Andrew Cranston is another. And now Jack Dunnett, one of the pupils Andrew taught at Grays School of Art in Aberdeen is beginning to flower with a very distinctive voice of his own - a visual voice, purely in paint, which is not at all easy to describe in words.A bit of context helps, a bit. Jack Dunnett was born in 1995 and was brought up in Thurso, a small town on the most northern tip of mainland Britain, where the ferry leaves for the windswept Isles of Orkney. His art gives the impression that he has always felt that he exists on the extreme edge of … I was going to write of everything, but that would be too simplistic. But then everything I start to write about Jack Dunnett's work I find to be too simplistic. Even his name. I was tempted, just now, to write 'Jack's work', but that would sound too personal and familiar. But referring to 'Dunnett's work' is too formal. His work is both individual and detached, so using his full name is more apposite.Back to the edge … of what? The edge, perhaps, of himself. His paintings are purposefully ambiguous. They spring in part from personal experiences but he wants these to remain inaccessible to the viewer. Yet at the same time he doesn't want the viewers to feel locked out but free to explore the piece and find in it what they will. This is an invitation and a distance. It is fundamentally true, too, of all human relationships, however intimate. We are each ultimately alone, however much we love another. This is the solitariness one senses in all Jack Dunnett's painting. It is, one feels, one reason why they are so small, and the edges of each image are so important to the whole.More facts. He can't remember when he didn't draw. An only child, his grandmother bought him a sketchbook when he drew on all the note-pads she used for shopping lists. From the age of about five, his father drew with him for half an hour in the evenings, pictures from life or their imaginations. He went to art school, not because he thought there was any chance of earning a living as an 'artist', but because he didn't know what else to do. He studied at the most northerly art school in Britain - another 'edge' - one of the few left that taught the techniques of painting and drawing. And, from there, he has never looked back.Visiting Jack Dunnett in his studio is an unforgettable experience. The silence around his thin, delicate form is almost palpable. He gives the impression of being haunted, quietly but relentlessly. This stillness is emphasised by the smallness of his studio, one of several - most presumably much larger - in a multi-storied artists' workshop complex near the city centre of Glasgow. You are immediately aware of a mind at work. There's a shelf of books in the corner by the window: volumes on his favourite artists, like Anselm Kiefer, Phillip Guston and Caspar David Friedrich, interleaved with books by Carl Jung and one by Freud. All look well-thumbed.There is mess, as you'd expect in a workplace, but even this is contemplated. Tubes of oil paints are hung up on clips in neat rows on the wall, top-down, ready for pressing from the end. Next to them are colour charts, post-notes and postcards of paintings he admires, among them a Schiele, Sickert and a Bacon. His painting trolley below is like Bacon's own studio in miniature, an explosive riot of paint, pots and brushes, and across his pallet, which is encrusted as thickly as an Auerbach, lies a builder's scraper, hinting that we are in the presence here, despite the order, of no ordinary, orthodox painter.To help pay his way through art school, Jack worked part time in a hardware store and became fascinated by the much rougher, tougher painting and decorating materials used in the building trade, far from the refined world of artists' oils, acrylics and watercolours. A chart of what can go wrong with household paints if they're misapplied, showing effects of leeching, rippling and blistering, gave him ideas. He didn't want to create art in a precious, let alone a pristine environment. So, he began to use raw materials, like cement and liquid rubber used for roofing and all manner of potentially dangerous chemicals. The chance effects of their applications inspired him, just as anyone has to responded to the random, disconnected incidents of ordinary life. These tough backgrounds give his little paintings scaffolding and guts, but the spirit that flows through them still come from the tubes of artists' colours hung so neatly along his wall.So, what's the result of this explosive conjunction? This is even more difficult to write about. Take the painting called The Well Worn Path of 2024. No one reading these words would expect to see a painting of a woman sitting in an armchair watching TV, which is what it is. His art is not, in that sense, at all literary. His titles are added later - they're more like associated but independent thoughts. There are lists of them hung on the wall, near his paint tubes. They read like poetry in themselves: Vinyl Frontier, Wishful drinkers, I'm eating my head, Here come the cowboys, The art of being a canvas, Flowers for hours, The sun always smells on TV. Some are crossed out; they might have been used, or become defunct.And yet the title The Well Worn Path is literal in a sense. The picture is painted on a surface of tattered, scumbled and scraped paint that looks exactly like a worn, threadbare carpet - hence the literal accuracy of the title. This basis provides the painting with its silent, moody atmosphere, in which a woman sits idly watching the TV screen. The fact that the TV is lit but has nothing on it - the luminous opacity of a blank screen has been beautifully rendered in paint - and the light from it that catches just the edges - edges again - of the woman's face, flesh and clothes, as well as the deep claret red of the wall behind which is contained, by implication, in the dark green bottle beside her green armchair - all of these touches of paint add other dimensions of implications to the painting's title.The Well Worn Path is a painting about a state of mind, in the same way that Sickert painted images of boredom. But to write that this little painting is about 'the meaning of a sense of meaninglessness', which in many ways it is, sounds tricksy and superficial, which the painting itself isn't, not at all. Phrases like this pat it and you on the back and say 'that's it'. They are dismissive, and allow you to move on. But this painting doesn't. It makes you want to go on looking at it. This is why writing about Jack Dunnett's is so difficult and deceptive. Words aren't right; looking is everything. He paints pictures that are alive, that you want to go on living with.And as you go on looking at The Well Worn Path, you notice the precision of the composition, the placing of the empty screen and the upright bottle (vertical features are vital elements in Jack Dunnett's art) and the angle and hue of the skirting board. These elements go on singing whenever you look at them. His paintings are lasting, in the same sense that poems are lasting. They are feelings and thoughts woven together so intricately and cleverly that they hold the fleeting moment still, as if in the palm of your hand. This is one reason why they are so small. He paints them like this too, he told me, holding the one he is working on in his hand, as he walks around the studio, looking at it from different angles in the changing light. So, his paintings hold time still, but they do this purely visually, not verbally. They are poems in paint, sensations that have to be painted, for there is no other way to contain them and express what they might mean.Even more significantly, Jack Dunnett's paintings are of now, condensations of what it really feels like to be alive today. They are works of art, not propaganda, pared of all hopes, however worthy, of what life ought to be. Here there is nothing woke. His paintings just try to get as close as possible to what life actually is. All his paintings are contemporary. They are replete with memories too, but then the present always is. One beautiful little painting I saw in his studio - not yet titled - shows in the background a modern housing estate over a slatted fence - very evocative of my own childhood, as it happens. The windows look like eyes all looking to the side, and one is broken - a black burst in white. An improvised goalpost is painted on the fence - a favourite repeating motif in his art - even games are temporary - but below is a primeval swamp, looking global in its scope. A boy jumps into it - what kid can resist a puddle? - while his shadow on the white water, dances, Matisse-like, with joy. This is memory in now.Though we can exist only in the present, we are facing backwards in time for none of us can see one minute ahead. Jack Dunnett's paintings are about that: our current and past sensations viewed within the context of our awareness of the inevitability of sweeping change. His most delicate brushstrokes indicate the former, while the latter is evoked by the primal chaos of his building-material bases. When I visited his studio there were a dozen or so of these differently coloured little bombshells lying on their backs waiting to be painted, acted or danced upon, often by figures looking further into the picture, not out. He told me he can work on up to fifty of these tiny panels at any one time - watchful for the moment when one demands to be painted - such is the wealth, breadth and depth of the inner sensations he is mining. And he's only just beginning. One can't help but think there's a cave of wonder still to come. -

-

Film